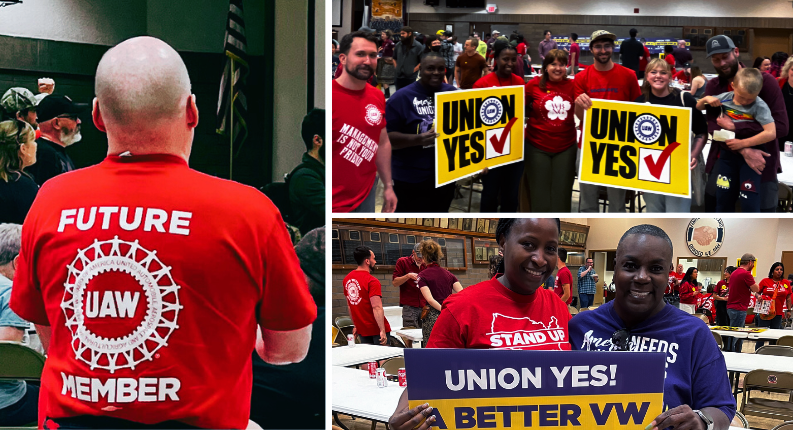

In the last six weeks, educators and school employees in politically red states have taken direct action to improve conditions for themselves and their students. Their militancy models what it means for working people to act like a union—regardless of how employers define them. Like the Memphis sanitation workers 50 years ago, these individuals took risks despite a lack of legal protections. And like those southern public sector employees before them, the bravery of West Virginia teachers was rewarded—in this case with a pay increase for all state workers. These actions earned the attention of many progressives and labor leaders. Teachers in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arizona have inspired many and reminded movement leaders of the power and resilience of working people at all levels, despite the limitations of the laws and institutions that are meant to protect and defend them.

For the overwhelming majority of the past century, a union contract has been the best weapon for working people to ensure they have access to staples of a social safety net such as health care, retirement income, and other benefits often provided in other democracies directly by the government. But these 20th-century protections have been eroded and even perverted into limitations to the democratic activities of the working majority. Corporations have re-organized themselves to more efficiently exploit the human labor and natural resources of the earth in devastating ways. National industries have given way to multinational production chains, just-in-time manufacturing, and compulsive labor migration patterns that maintain the companies’ flexibility needs.

And yet, many non-union workers and union members in right-to-work states are demonstrating practices that could engage millions of people who lack access to a union contract. Like their forebears, they are creating a new democratic platform for having a say, as equals, over their conditions without waiting for the perfect legal framework to protect them. After all, even in the heyday of the National Labor Relations Act, an overwhelming majority of workers won the ability to form unions through militant action, not through an elections process. And today, the more corporations and billionaires rig the rules to interfere with people’s ability to collectively bargain, the more nimble and innovative the modern labor movement has become. They are building a 21st-century labor movement.

Birthing a new framework for collective bargaining will not happen simply by rallying only those who already have access to 20th-century rules and protections. Certainly, unions and other institutions must safeguard what they’ve won. But right-wing extremists, big business, and their friends in elected office and the courts have blocked and eroded most of the traditional channels for the remaining 90 percent plus of working people who seek to form unions. Building organizing and collective bargaining power in this modern age requires creativity and risk for establishing a bargaining framework that goes beyond the New Deal-era bedrocks. We must expand how working people collectively negotiate together, the types of binding agreements they can win, what they can bargain over, and who they can bargain with to assert their power and voices in the workplace, in their communities, and in the future of our society as a whole.

And teachers now join food service employees, retail associates, and many others in leading the way.

There are many people in a state of shock and awe in response to the teachers rising up in states with some of the harshest labor laws on the books and governed by some of the harshest critics of unions and working people. If their analysis is guided only by knowledge of the traditional electoral map and game plan, their reaction is to be expected. I argue that if we look through the lens of different criteria, their actions come as less of a surprise.

It is not enough for working people to elect good, or good enough candidates into office to represent them. Ultimately, working people seek the ability to govern in ways that maximize everyone’s democratic participation and practice—at work and in their communities. We need a path to address how we galvanize their power to organize, negotiate collectively, and govern in all aspects of their economic and political lives—far beyond the mechanisms of the current electoral channels and traditional collective bargaining agreements.

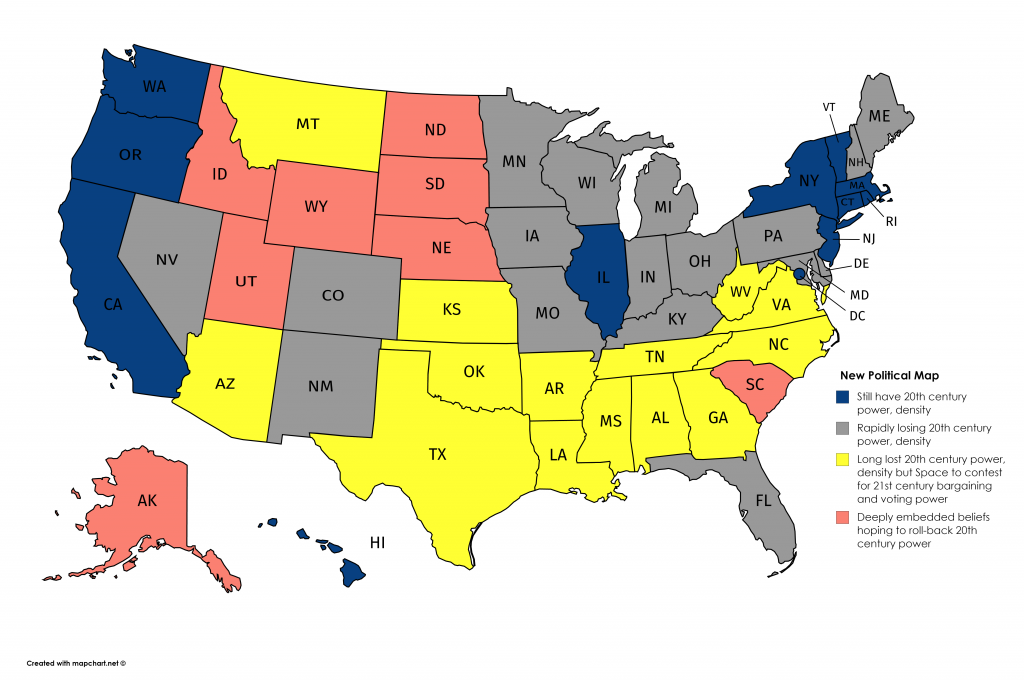

We must offer guidance on how to engage working people in the entire country so our movements can build power—both at the ballot box and directly with capital through expanded forms of collective bargaining. I offer that a different map is necessary to understand the recent upsurge in red state activity, a map that defines states not by the political leanings of their congressional delegations but by their relationship to 20th-century democracy and its prescribed protections.

First, there are the states that still have robust infrastructure and protections for working people’s right to vote and collectively bargain based on 20th-century laws and regulations—noted in blue in the illustration. These areas, such as New York, Massachusetts, and California still maintain robust union density. They have contentious primaries, including viable left-leaning candidates. And they boast a rich tradition of groups representing a popular majoritarian ideology which influences public opinion about the role of government, corporations, development, and workplace democracy.

Progressives in these areas must continue to exercise their existing power through the current channels and institutions. They can still win in ways that model how we make our values real in the world and expand what people believe is possible.

The states noted in grey—many in the Midwest—represent areas that have experienced a recent and rapid erosion of protections for the voting and bargaining rights they enjoyed in the 20th century. Individuals in these areas still have an institutional memory of the power they used to have before the plant closed and the law changed. Aside from being incredibly angry, many in these communities are skeptical not only of the old institutions that they feel betrayed them but may also hesitate to embrace any untested strategies for building power. In some of these states, working people can still win based on the 20th-century rules—though less and less often.

Movement leaders in these areas should accept that the old system did not work while also moving new strategies and campaigns. Such efforts can yield small victories to rebuild momentum and morale while also building organization, especially as communities in these regions recognize and still relate to various cultures of organizing.

The pink states indicate the jurisdictions that have both long lost (if they ever really had) most 20th-century protections for the ability to vote and negotiate with capital and that have little movement organization to confront the deeply embedded Right. The first instinct for progressives might be to give up on people in these areas. In comparison to other regions, the pink state populations are quite small, and the requirements for winning and losing an election are less complex. In these states, progressives should consider how they build a base among people who share our values—creating visibility for opposition forces in some of the most difficult political terrains with the goal of discrediting the radical Right while developing new movement leaders to move their own strategic campaigns.

Last, many of the states highlighted in yellow have been written off by national progressive actors since the U.S. Civil War. These states have long lost (if they ever really had) most 20th-century protections for the ability to vote and negotiate with capital, whether explicitly by southern property owners and businesses that enacted right-to-work laws or implicitly by the Right’s systemic disenfranchising of formerly incarcerated people in states with large black and brown populations.

Most working people in yellow states have little to lose and everything to gain in a struggle for power. And in those areas where they have come together to struggle against the existing power structure, they often demand far more than a return to the old system of organizing, bargaining, or even voting. West Virginia teachers negotiated far beyond their immediate needs to transform funding for schools and conditions for students. The reward for their risk? A five percent wage increase for all state employees. Indeed, some of the most exciting and militant upsurges are happening, among teachers, students, and many others in yellow states. Since the looming threat of Friedrichs vs. California Teachers Association and now Janus vs. AFSCME Council 31, several public sector unions have reported significant growth of volunteer membership in these regions.

The same is true in the political arena. In yellow states like North Carolina, labor movement leaders and activists are not just making demands to repeal right-to-work laws, or uphold the right for individuals to vote. They’re insisting that the people they represent who live, worship, and work in their region have a collective, democratic voice in the how their government runs and how voting districts are drawn.

Progressives can support and re-enforce local struggles in yellow states where working people are exposing the failings of the existing regimes and structures while also re-defining the social contract in ways that establish modern rules for governing, voting, organizing and bargaining—essentially, the foundations of democracy. Coordinated victories in these states could change the national paradigm in favor of working-class organizations.

Through the lens of this map, the recent upsurge of teachers, students, and many others who reside outside of the more traditionally progressive states is not surprising at all. Working people in these areas are building new systems for democratic participation in society and the workplace. In a way, these areas are frontline sites for building 21st-century power. No working class community is left behind in defining the future of democracy.