An introduction to strikes in the labor movement, how they work, and how they are organized. Featuring an overview of meaningful strikes throughout history and resources from the Jobs With Justice library for easy use by organizers, researchers, and educators.

@jobswithjustice What is a strike? Why do they matter? What does it mean when workers take action like this? Check out our #Strikes 101 video to learn more and how the Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike continues to inspire workers to take collective action today! #atlanta #strikes101 #blackworkers #domesticworker #laborhistory #workerorganizing #howto #strike #afrobeats ♬ love nwantinti (ah ah ah) – CKay

Enjoyed our TikTok mini-lesson? Read the full article below.

What is a strike?

A strike is defined as the collective action of withholding labor to pressure those in power to improve the workplace. Strikes are an impactful tool to bring workers together to influence the terms and conditions of their employment.

Workers strike to protest unfair labor practices and violations of labor laws – some common examples include refusing to recognize or negotiate with the union, union busting, and wage theft. Workers also strike when employers fail to reach an acceptable collective bargaining agreement with the employees in union. Because of the personal and collective sacrifices striking requires, union members hold a vote on whether to strike – many need a two-thirds majority vote to formally strike.

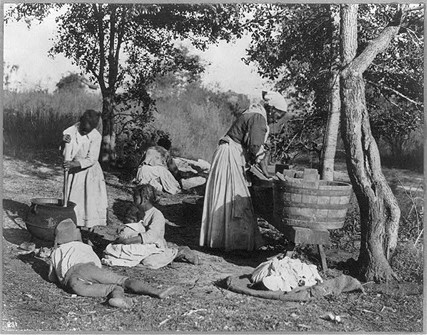

The Atlanta Washerwomen’s strike in the summer of 1881 is a strong model of collective action and how to organize effective strikes. It was one of the largest Reconstruction-era strikes in a Southern city led by formerly enslaved Black women who did the laundry for families across Atlanta. It is critical to include the Atlanta Washerwomen’s strike as part of labor history. The strike served as the foundation for collective bargaining that followed for hotel workers, cooks, maids, nannies, and other members of the Black working class across Atlanta and ultimately across the country.

Strikes in History: Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike

Inspired by the Black women who formed Mississippi’s first labor union almost 20 years prior, the laundresses and washerwomen of Atlanta joined together in union as the Washing Society on July 19th, 1881 at what is now the Wheat St Baptist Church. [1] With the support of local pastors, they began a strike to demand higher wages and dignity at work. It was less than twenty years after the Civil War.

“…the powers that be in Atlanta wanted to build on the system of labor carried over from the Old South, one where Black laborers were held in subservient roles with strict white oversight and supervision – not to mention social and political disenfranchisement. Black women’s labor (teachers, nurses, household maids, laundering, etc.) was sought after. What was not guaranteed were equitable working conditions, dignity, respect for their expertise, and a fair wage.”

–Jessica Edwards & Josie Walwema, “Black Women Imagining and Realizing Liberated Futures”, 2022

At that time, most of Atlanta’s Black female population earned wages as domestic servants – the labor relations established by chattel slavery had not yet shifted.

Doing laundry for wealthy, middle class, and even poor white families across Atlanta was a laborious task that included making one’s own soap from scratch and building wash tubs out of old beer barrels as well as collecting garments, hauling water, ironing – seven days a week. The strenuous work earned washerwomen as little as $4 to $8 per month. [2] Employers were known to reduce their wages or even refuse to pay if washerwomen’s skirts were muddy or marked when they arrived to drop off laundry.

In order to demand respect and higher wages, ”[The Washing Society] drew on leadership and political skills formed during Reconstruction in Republican party activities, labor associations, secret societies, and informal neighborhood networks.” [3] The women held large convenings in Black churches like Wheat St Baptist Church, and smaller neighborhood meetings in each ward of the city.

Their demands? One dollar per dozen pounds of laundry and a city license to protect all laundresses’ wages.

The Washing Society canvassed neighborhoods to build support and power for their strike. The methods ranged from door knocking and inviting other laundresses’ to ward meetings to confrontation [4]. White newspapers heavily criticized the use of militant direct action like the Atlanta Constitution, which gave the union the nickname “Washing Amazons.” However, their tactics were highly effective in building the necessary power for the strike to win. Without that level of escalation, employers would have paid scabs to break the strike, and wages may have remained optional for washerwomen. Using both militant and democratic strategies, they built their strike from 20 members to over 3,000 members in only 3 weeks.

The Washing Society invited white washerwomen to join their strike, as well as hotel waiters, cooks, maids, child nurses, and non-washing women of Atlanta. The show of interracial solidarity was also historic at the time, as 2% of white washerwomen in Atlanta also joined the strike.

Businesses fought to break the strike – white families tried to hire strikebreakers, landlords raised striking tenants’ rent, and police harassed, fined, and arrested members. Even the city council gave tax breaks to industrial laundromats, trying to make the washerwomen obsolete.

Things came to a head that August, months before the International Cotton Expo, would bring thousands of visitors to Atlanta. Undaunted by the police intimidation and economic pressure of local white businesses, The Washing Society signed a letter to the mayor on August 1st, saying:

Dear Sir:

We the members of our society, are determined to stand to our pledge and make extra charges for washing, and we have agreed, and are willing to pay $25 or $50 for licenses as a protection, so we can control the washing for the city. We can afford to pay these licenses, and will do it before we will be defeated, and then we will have full control of the city’s washing at our own prices, as the city has control of our husbands’ work at their prices. Don’t forget this. We hope to hear from your council Tuesday morning. We mean business this week or no washing.

Yours respectfully,

From 5 Societies, 486 Members

The Washing Society threatened to escalate to a general strike of domestic workers in the city during the Expo if employers did not meet their demands. And that was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Worker power always wins

Following their letter to Mayor English in August, the Atlanta Constitution reported that the Washing Society pay $25 to the city and became licensed to raise their wages with legal enforcement.[5] Some accounts contradict this outcome, saying that the women ran out of strike funds before the city conceded to their demands.[6]

Either way, the strike remains historic in scale and context. Thousands of Black women fought to win a union during Reconstruction–in 1881–with chattel slavery barely in the rearview mirror. The workers won because the city could not function without them, and because of their effective communication and organizing – their strike is an excellent model of how to exercise that power.

Today, workers don’t only strike for wages and benefits. Teachers strike to improve class size, warehouse employees strike over unsafe conditions, and machinists strike to keep jobs from going overseas. Strikes are a last resort by employees wanting to resolve a major labor dispute with their employer – when workers have exhausted all other options, it’s time to take action.

Footnotes:

[1] Atlanta Constitution, “The Wet Clothes”, July 29, 1881. [2] Brandon Weber. “‘We Mean Business of No Washing’: The Atlanta Washerwomen Strike of 1881”, 2018. [3] Eric Arnesen, “Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History”, vol 1, 2007. [4] Atlanta Constitution, “The Wet Clothes”, 29 July, 1881. [5] Tera W. Hunter. “To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War.”, 1997. [6] Dorothy Sterling. “We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the 19th Century”, 1987Take action with working people today by becoming a member of Jobs With Justice’s Unified Action Team. Follow us @jwjnational on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok for more #Strikes101 lessons!

Read the policy one-pager Strikes 101 for more information and context on strikes in the labor movement.